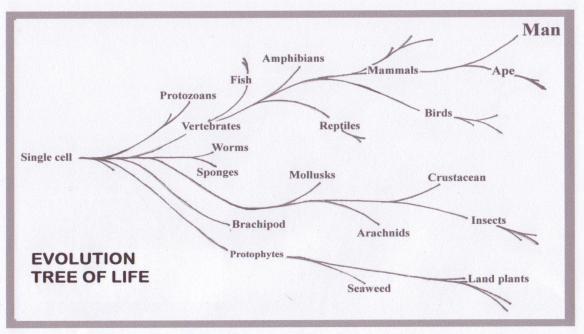

In his book Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History, Stephen Jay Gould discusses the impact of iconography on the way we interpret data. By iconography he means visual representations of our ways of thinking. His argument is that the visual depictions of evolution as the March of Progress or the Tree of Life not only are a misrepresentation of evolution, but also impact the way scientists themselves interpret data.

The March of Progress has become a visual trope used in a variety of mediums. The idea is to show the gradual evolution from primitive organisms to more complex, “evolved” organisms, culminating in modern man.

This trope is used in popular culture a lot, as in this amusing example I included for the Dr. Who fans.

The March of Progress, along with its analogue, the Tree of Life, is wrong. It promotes the idea of evolution as a progression from disorder to order, from simple to complex. It hides the actual complexities involved, and causes scientists to try and shoehorn fossils into a place on the tree of life as ancestors of modern creatures.

Modern paleontology had to undo and reinterpret much of the work done by earlier scientists who were wedded to the idea of evolution as the March of Progress, and who therefore tried to fit morphologically distinct organisms into the Tree of Life. In fact, as Stephen Jay Gould likes to point out, evolution looks more like a bush (although I think it looks more fern-like). After the Cambrian explosion, there were more than twenty kinds of arthropods that have no living descendants. These different body plans died out in the Late Devonian extinction, leaving only the current four families of arthropods. (Arthropods are a phylum of invertebrates which currently is made up of spiders, insects, crustaceans, and myriapods like centipedes.)

I find this argument fascination, as it provides an interesting way to think about the functioning of religious iconography. Take, for example, this representation of Jesus that is popular with Protestants. This Jesus has distinctly European features with classic movie star good looks.

If you think about this theologically, you’ll notice that the Protestant Jesus looks like us. He is clearly human; this representation provides no clue to His divinity. This is a Jesus you could have a crush on, a Jesus who would not be out of place in People magazine. In addition, the Protestant Jesus is not looking at us. While we are gazing at Him, He is gazing elsewhere. This Jesus is seemingly not engaged with us; he does not look at us with either compassion or judgment.

By contrast, Roman Catholic versions of Jesus are often more sentimental. One stylized depiction is called The Sacred Heart of Jesus, and is often used by various Roman Catholic Churches. In this depiction, Jesus has classic European features but is somewhat effeminate looking. He is gazing out at us with love. Catholic devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus has to do with the human and Divine Heart of Christ, particularly as it represents and recalls His love for us. This painting is designed to use as an aid in stirring up our imaginations and increasing our devotion to Christ.

Note, as well, the aureola (halo, or glory cloud), representing the holiness of Christ. While this Christ is clearly human, the aureola serves to indicate His divinity as well. Like the Protestant Jesus, Catholic representations of Jesus pay great attention to representing the humanity of Christ. Christ and his surroundings are painted so as to simulate reality. This is true even in their stylized depictions of the crucifixion.

The crucifixion is often depicted with a certain sentimentality. This Christ is the object of desire. As such, this is not the Christ of scripture, the one who has no beauty that we should desire Him. This is not the Christ who had been beaten and scourged to the point that he was unable to carry his own cross. And this Christ is, once again, not looking at us with love, but looking up to heaven. The intent of this painting is for us to use our imaginations to stir up our devotion to Christ.

Contrast this with one of the oldest extant representations of Christ the Pantocrator from St. Catherine’s Monastery, Egypt. This is a representation of Christ as God Almighty, the Lord of Hosts. This icon famously shows the two sides of Jesus. On the left side, He is looking at us with compassion; on the right side, with judgment. Instead of a standard halo, we see Jesus depicted with a halo containing a cross, although only three arms are visible. These three arms represent the trinity. On each arm is written one of three Greek letters (omega, omicron, nu) representing the phrase “He Who Is”. This phrase reminds us of The Name of God as revealed to Moses: “I am that I am.” Jesus Christ is God, and His existence is not contingent on anyone. We, on the other hand, do not exist of ourselves; our existence is contingent.

Note the position of the hands. Jesus right hand is held up in blessing, with two fingers extended (representing the divine and human natures of Christ), and with the ring finger and the little finger touching the thumb (representing the Holy Trinity).

There is much to love about this depiction of Christ, but there is no sentimentality. This Christ is gazing upon us, just as we are gazing upon Him. This is the Christ who is the Captain of the Host, the one who could have called upon 12 legions of angels, but who at the same time is involved with us.